The great rock tomb of the vizier Bakenrenef (L 24) has been investigated since 1974 by the University of Pisa under the direction of Edda Bresciani. The work still continues, funded thanks to the contribution of Cultural Relations Office (Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs).

The tomb is placed a few hundred meters south-east of one of the most famous monuments in the world, the step pyramid of Pharaoh Djoser of the 3rd Dynasty (2617-2599 BC), and is excavated in the north cliff of Saqqara, which looks the plain of Memphis.

The owner of this tomb is Prince Bakenrenef, son of Padineit, and vizier of Psammetico I, founder of the 26th Dynasty (664-624 BC). The whole complex (the façade, the vestibule, the long hall with pillars, the offerings chamber, the shrine flanked by two small cella) is dug in the rock and was originally covered with beautiful limestone blocks.

The archaeological exploration, begun in 1974, was intended to protect and restore this degraded tomb, which is so important for the original richness of decoration and its dimensions (40 m length, with 16 m deep shafts). The hypogaeum is preceded by a courtyard with the entrance flanked by pylons; the courtyard and the pylons were discovered by the Pisan archaeological expedition, but the pylons are now hidden under a modern road; sand and debris cover the cliff and the access to other underlying rock tombs.

The tomb was discovered by Jumel in 1820. Since then, it was admired by famous visitors of the 19th century, such as J.F. Champollion (the decipherer of Egyptian hieroglyphs) and Ippolito Rosellini (father of Italian Egyptology) during the French-Tuscan Expedition in Egypt and in Nubia in 1828-1829. Rosellini, in his “Giornale”, described the tomb as the most magnificent tomb of Saqqara. In 1828 he bought the Bakenrenef’s limestone sarcophagus in Alexandria and moved it to Florence, where it can still be admired in the Archaeological Museum (Cat.1705 / 2182).

In the last century, before the work of the University of Pisa, the tomb was accessible through the sand, arriving at the beginning of the pillared hall. The inside of the hall was already deteriorated, as shown by the precious drawing of J. Gardner Wilkinson, reported in his “Manners and Customs” (1854). The pillars had no covering blocks and the ceiling was almost completely collapsed, whereas the jambs, the lintel and the lunette of the gate opening to the offering chamber were still intact.

The tomb of Bakenrenef was recorded by Richard Lepsius in 1843 (Denkmäler aus Ägypten und Ätiopien 1848-1859). At that time, the pillared hall and the other interior rooms were in fairly good condition and Lepsius could copy scenes and texts of the covering parts still in situ. Nevertheless, he did not provide a copy of the lunette drawn by Wilkinson.

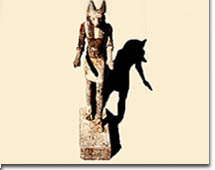

Since the last decade of XIXth century, the covering blocks of the tomb were gradually taken away by antiquity thieves and sold abroad, especially in the US (Metropolitan Museum of New York, Field Museum of Chicago) and Europe, even to private citizens. Other objects coming from the tomb are known, including two statues. One, representing Bakenrenef, belongs to the old Hoffman collection, while the second one, a beautiful statuette about 36 cm high, is divided between the Musée d’Art et Histoire in Brussels (upper part), and the Brooklyn Museum (lower part); the vizier wears a necklace with an amulet descending on the chest and a striped wig with lateral braid typical of the Ptah’s sem priests.

Furthermore, a libation basin is kept in the Cairo Museum. It presents inscriptions on four sides with the typical texts of this type of object and its cavity could contain more than 26 liters of liquid. It was placed in front of a statue of Bakenrenef, probably in the offering chamber. When the University of Pisa began the archaeological excavation of the tomb, the covering blocks were almost completely taken away, but some ceilings remained intact, witnessing the past beauty. In addition to robberies, there was the damage caused by the alteration of the poor-quality Saqqara rock. Due to this problem, even the architect of Bakenrenef had to modify the original project. For example, the great pillared hall was originally planned with eight pillars, which were then reduced to six. Furthermore, in a later period the façade collapsed and retaining walls were built in the vestibule. Some decades before the archaeological expedition of the University of Pisa, blocks and fragments taken from the tomb were spread out in European and American museums. Most of these have been traced. Part of the decoration is in situ and hundreds of blocks and fragments left by the thieves have been found during the exploration of the tomb since 1974. The investigation in the shafts and tunnels of the tomb brought to light unknown rooms, such as the gallery of the south shaft, called the gallery of the vizier. Four beautiful sarcophagi with carved hieroglyphic texts were found there. A demotic text on the gallery wall informs us that it was inaugurated during the reign of Nectanebo I (30th dynasty) by a descendant of Bakenrenef, the vizier Padineit, called Pascerientaihet, son of Horiraa.

Many archaeological expeditions have allowed us to understand the different construction phases of the tomb, its transformations and the restoration and consolidation attempts made in ancient times. In addition, they have also allowed us to better understand the project of the architect, who seems to have taken as an example the Theban Tombs (of royals and nobles) of the period between the end of the 25th and the beginning of the 26th dynasty. For the decorative program of the tomb, however, he used style and themes of the Saqqara mastaba (archaizing decoration of façade, vestibule and offering chamber with two “pancarte” or offering lists) alongside “modern” style and themes of texts and illustrations of the “Book of the Dead” (other rooms of the tomb).

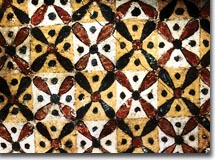

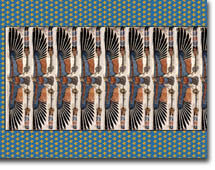

The ceilings show a varied decoration: astronomical motifs in the vestibule (where we read the cartouche of Psammetico I), low relief and painted figures personifying the hours of day and night venerated by the vizier in the pillared hall, and tapestry motifs, stars, royal vultures in the other rooms. The Old Kingdom style decoration of vestibule and façade was discovered by the University of Pisa, which, in 1978 and 1979, found many blocks reused in the retaining walls built in the Greek-Roman period. Furthermore, a part of the vestibule wall decoration was found in situ.

In 1975 the University of Pisa found another tomb, the BN2. It shows no wall decoration but have a beautiful limestone portal with beautiful sculptures. The owner, depicted on the architrave of the gate, is the priest of Sekhmet Pascerientaisu, who lived in Memphis in the 4th century BC. The hieroglyphs on the jambs report two important texts: a hymn to the rising sun and a hymn to the setting sun.

The exploration of shafts and lower galleries gave a lot of beautiful wooden furnishings, sarcophagi and precious amulets. The expedition register has more than a thousand objects, including those from the tomb of Bakenrenef, used as a family tomb for more than a millennium, and those from the tomb of Pascerientaisu. Most of these objects are important documents for the history, art history and material culture of Late Period in Egypt. All the material is stored in the expedition warehouse in Saqqara, with the exception of the wonderful painted burial cloth found in 1975 in the southern shaft of Bakenrenef’s tomb, which is now exhibited in the Cairo Museum (J.E.Prov. 9/12/95/1).

Finds from different eras and monuments have also been discovered: the sandstone block with sculpture from a temple built by Sheshonq I (22nd dynasty) in the Memphis area, and the large and fragmentary naos stelae with the three figures in relief of the Osirian triad and the cartouche of king Shabaka (25th dynasty), whose pieces have been reused in the Late Period façade.

In 1982-83 problems of stability dissuaded from continuing the archaeological investigations of unexplored tunnels and shafts. A project was developed: the preliminary consolidation of the geologically compromised complex was carried out together with the anastylosis of the tomb covering rocks and of its architectural elements.

Thanks to a first contribution granted by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs – Development Cooperation Department to the University of Pisa, the first phase of an Italian-Egyptian cooperation program, the “Saqqara school site”, began. It was an experimental archaeological site with stages for Egyptian technicians on restoration, conservation, cataloging, modern technologies, which was inseparably linked to the “Saqqara Project” for the restoration of the tomb of Bakenrenef. The University of Pisa completed the first phase of the Program (1985-1987) but the subsequent phases were not financed and therefore the consolidation project remained unfinished.

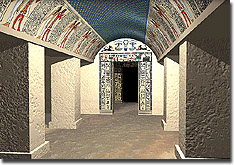

The overall program for the three-dimensional reconstruction of the monument is still ongoing. Below we want to show the work in progress, and therefore only some of the parts advanced enough. The façade of the tomb of Bakenrenef, its courtyard, and its entrance pylons have been reconstructed. So far, only a drawing of the vestibule ceiling has been proposed. It is currently covered with lampblack which makes it unreadable, but non-blackened sections were found during the investigation. The reconstruction shows the original aspect of the pillared hall and of the Vizier’s underground funerary chamber, with the relocation of the sarcophagus. The three-dimensional model of the tomb, based on the perfect architectural documentation carried out during these years of work, was designed to relocate on the walls some “tables” from Denkmäler by R. Lepsius. These were used as reference in this experimental phase and they were painted with colors confirmed by the existing parts of the tomb. In fact, a partial virtual reconstruction has been preferred until now, to allow people to enter the rooms of the tomb “with Richard Lepsius”, seeing things the German scholar saw a century and a half ago. In the shrine we went beyond the Lepsius model: we interpreted and completed the statue fragment that Lepsius was not able to identify, placed in a beautiful frame on the back wall. The proposed hypothesis is that of a large statue of Hathor-cow that could have in front of her, in act of protection, the figure of the tomb owner, according to a type of sculpture well attested for the Saitic Period. The hypothesis is based on the outline of the stump and on the fact that the high double feather, with the solar disk that is usually carried by Hathor-cow, would explain certain traces in the central axis of the shrine ceiling.

The 1996 archaeological season was full of important results, thanks to the work carried out by a group of paleopathologists of the University of Pisa, directed by Prof. Gino Fornaciari, who collaborated with the Egyptologists, especially with Dr. Flora Silvano. They analyzed the human remains, both mummified and skeletal, coming from a wooden coffin (3.14 m length, 0.70 m width) found in the north shaft in 1977 and belonging to a lady who lived in the 26th dynasty. Her family relationships with Bakenrenef still must be clarified. From the texts on the coffin we know that she was called Merneith (indicated only as Osiris), that his father was “the director of the palaces, Ugiahorresnet”, and her matronymic “N (y) -s-it-s-Ra”. Merneith’s mummified body had been filled with resins. In the correct anatomical site a “heart scarab” in hard green stone was inserted, with no inscriptions (3.15 × 2.3 × 1.17 cm) and carefully wrapped in bandages. The X-ray of the mummy has also identified a round package of resin and other material (no organs) in the abdominal cavity.

During the same season in 1996 two other deceased were examined: a man and woman who lived in the Ptolemaic Period, whose double burial was found in 1979 at the entrance to the east tunnel of the north shaft. Even for these individuals, the paleopathological study gave valuable information revealing that the woman was suffering from bone tuberculosis and the death was directly caused by the disease.